Dev Raj Dahal

Senior Political Scientist, Nepal

Ironically, the appetite of Nepali leaders to invite foreign intervention for regime change has institutionalized external interest in every public institution without any sign of an exit. It has unveiled a policy paradox: political leaders of all political parties have officials endorsed liberal worldviews set by democracy, human rights, mark economy, justice and ecological renewal embedded in the Constitution of Nepal and received cooperation from the democratic community of nations in party building, fostering NGOs and civil society and cultural transformation. This has opened the impact of the Western nations soft power inflicting national cultural cringe while leaders, cadres and intellectuals of the left parties are getting training and exposure on the relevance of Xi Jinping Thought for Nepal’s speedy progress. China favors the Nepalis for the choice of their polity, supports sovereignty and eschews cultural transformation as it is reviving Buddhism. This has created contradictions within left political parties and even polarized their stand on Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) and the Venezuelan crisis. Similarly, business and elite interests for globalization where Nepal has less advantage made its economic diplomacy either an internalization of external interests or externalization of the nation’s labor and capital, not a win-win approach. It is a double-win for outside powers and a drain on national construction.

National freedom of diplomatic maneuver becomes a charade if its domestic politics is deeply mired in the crisis of governability permeated by external interests either directly or through advice and project aid even by proxies with interests in bureaucracy, politics, civil society, business, NGOs and professional organizations. The covert or overt influence by one state in the internal affairs of another is inherently immoral but it is not new in Nepal. Flows of foreign aid follow not only humanitarian, equity consideration, economic and technical interests but the geopolitical interest of donors as well. “Aid working against four above considerations, as had been found in the past, should be regarded as only a burden to the Nepali society keeping it in a debt trap, low equilibrium population trap and, hence, inflation-augmented hardship trap” (Sharma. 2000: 85).

The shift of aid to the alignment to national priorities has yet to take place to augment Nepal’s political and policy sovereignty. Powerful Western donors have imposed political conditionalities for economic assistance to Nepal aiming to foster common values, institutions, educational, administrative and security practices befitting changing geopolitical imagination. This has invited their non-Western counterparts especially India, China and Russia to follow suit in Nepal where it wants to profit from both sides without decoupling from either. Neither India, nor China nor even Russia has an interest in defending democracy in Nepal, the shared political ideal of many Atlantic nations (Bleie and Dahal. 209:4). The Indian media and political leaders often allege and voice fear of the proliferation of Western INGOs, NGOs and civil society and their concentration in Nepal’s southern flatlands, simmering with discontent between secular leaders and the His Muslim local population. Buffering the frontiers is important to es the region turning into “shatter belts” which once housed116- non armed actors and witnessed a series of communal strife. India perceives the meddling of outsiders in Tarai a drain of their soft power of spin and social capital which glued Nepal-India civilizational affinity sort of common security community.

The great power rivalry to influence Nepali top leaders has its vital national center, its heartland, weak and vacillating many of its state-bearing institutions are rendered partisan, unable to exercise their integrity, authority and legitimacy and formulate con policy. Only Nepal Army remains the state-bearing national institution autonomous of partisan politics. An effective response to state-building needs the national leaders to size up the situation and take advantage of future economic opportunities. It is possible by formulating a for policy based on enlightened public and national interests and harness its internal resources for political stability, transit diversification expansion and accessing world markets which until in the past was languished in the international backwater. Nepal’s tree hugely imbalanced: import is 92.45 percent while export 7.55 percent and trade deficits amount to $11, 37 billion in 2019. In this smallness amounts to feebleness, requiring Nepal to walk on tightrope between stronger states temptation to promote free and small states’ imperative to distort it by promoting certain scale protectionism.

Nepali leaders need to adroitly balance internal equity, live and development needs and cope with external demands for consistency with their foreign policy goals, improve the quality of the nation’s institutional and intellectual muscle relative to the complexity of globalization milieu and pursue subtle art of steering diplomacy is for its own way of life, liberty and identity. Civic nationalism in democratic citizenship is an inclusive concept suitable for eve small state for adaptation in turbulent times. It projects the hi view of society, rejects subsidiary identity politics that reduces identity to primordial considerations, abjures the re-tribalization population lacking awareness of common ground for conflict resolution, spurs robust nation-building and boosts higher scale of progress international cooperation.

Nepal is an ancient state with a great promise and profound heritage of a culture of tolerance to diversity and asylum-seekers. But now it has been mired in pre-politics of strong leaders and weak institutions and anti-political tendencies of comprador classes, free-riders and middlemen having no stake in the nation’s future though they control the lever of political power through their nexus to powerful interest groups, top leaders and bureaucracy. They seek to de-politicize national awareness by suppressing the teaching of history, heritage of tolerance of diversity, national culture, political science and national values. The creation of externally-financed think tanks, education departments and faculties whose curricula conform only to the funders’ narratives and contest national security, nationalism, national identity, values and institutions can hardly secure essential knowledge and wisdom relevant for long-term foreign policy planning of this small state. Obviously, the Nepali state now confronts the ongoing clashes of culture, identity and solidarity. National perspective demands reflective socialization, innovation and inquiry of its foreign policy experts, public institutions, universities, cultural industries, International Relations Committee of the House of Representatives and the National Security Council which can regularly offer a synthesis of theoretical and policy-relevant inputs on every issue of vital public and national importance and evolve a common security, economic and foreign policy strategy.

Continuous political education rooted into its tradition of enlightenment and the zeitgeist to people, professionals and leaders can transform them into active Nepali citizens, create common background conditions for the rational resolution of clashes of all sorts and rescue the leaders from the blunder of geopolitical opportunism played on the clashing dynamics of regional and global politics creating disbelief, distrust and deadlock. It is opportunism affirmed by the joint statement of five ex-prime ministers of Nepal who had opposed external meddling and favored national self-determination in internal affairs of the state but did not name the meddler even promising not to turn back the clock of foreign intervention in the future. So long as external support for regime change remains in Nepali politics, mutual blame of Nepali leaders will continue to polarize domestic politics and hold back its foreign policy effectiveness and legitimacy.

Nepal also suffers from distortion in the epistemology and economy which have caused a delay in the implementation of human rights issues of transitional justice and reconciliation and post-conflict, post-quake and post-pandemic recovery and rebuilding. An enduring commitment and concrete action plan to improve the state’s ability to deploy nation energy in vital areas can enhance diplomatic effectiveness. A number of factors are, however, hitting the nation’s fault-lines created by se of gaps between the capital city, Kathmandu and the periphery, and Tarai, government and opposition, across the empirical divisions of social classes and multi-level governance over the issues of la resources, power and identities. The democratic prospect needs abiding hope of citizens that they can make a clean break from bad governance backed by kleptocracy, patronage and impunity politics of negation of the other and weak rule of law. Without break, it is hard to buttress suitable development policy and acquire an ability to rebalance foreign policy strategies. Reconstruction of national identity of citizenship requires the liberation of Nepalis from the incubus of a virulent partisan frame through the re-socialization and democratic reciprocity of leaders and citizens. Only a democratic government imbued with civic nationalism can be the best vehicle “reconciling conflicting demands in the society and, more importantly, improving collective well-being” (Chang, 2011:260) of Nepalis. This helps to gear up the state’s strength to provide an answer in response the globalization processes.

Concluded.

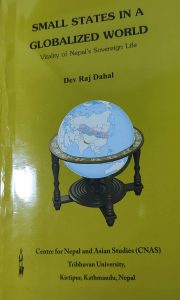

Text courtesy: Excerpts from the recently published book, (2022) “Small States in a Globalised World”, by Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS), Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal.

# The entire editorial board of the telegraphnepal.com is highly indebted to the senior political scientist of Nepal, Professor Dev Raj Dahal and the Executive Director of the CNAS Dr. Mrigendra Bahadur Karki.

# published in the larger interest of the global audience: Chief Ed.

Our contact email address is: editor.telegraphnepal@gmail.com