Professor Tone Bleie, Norway

Onset of a biting cold in the High-North:

In the Arctic capital Tromsø on 69.6492° north last week gave us a welcome spell of spring. A warming sun began melting one meter of hard packed snow. Suddenly temperatures fell drastically. Since yesterday we found ourselves again in a frozen white land.

The overnight shift may seem like a pregnant symbol for Norway’s foreign policy shift, and indeed the High-North’s from cooperative civil and military relations with neighboring Russia to an onset of a cold war climate.

I shall confine my discussion to some regional background and emerging consequences for Nordic peace and security. For reasons of limited space, I reserve for a later op-ed addressing dramatic repercussions for the economy and people-to-people relations in the Varanger region bordering Russia, repercussions which admittedly occupy very much my Varanger students and certainly not less our region’s politicians and industry leaders.

Many South Asian colleagues are asking me pertinent questions about Norwegian reactions to the war in Ukraine, noting rightly that we share a border with an assertive Russian Federation.

This 198 km-long border winds through a predominantly riverside and forested terrain, guarded by about 200 soldiers on each side. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is triggering an alarmist polarized public outpouring of the liberal “West” encountering an aggressive revisionist Russia. Many Norwegians have come forward, willing to help by accommodating Ukrainian refugees.

Norway has so far received 16, 000 of them and plans for a scenario of a total of 60, 000. From a vantage point as global analyst on issues of international law, peace, soft and hardcore security, neither massive alarmist reactions nor the sudden outpour of empathy with refuges with whom we can easily identify are sources of much comfort and reassurance.

For five consecutive years democratic Norway has topped the free press index of The State of the World Press, followed by Finland and Sweden. Beyond this impressive ranking is a less reassuring reality.

The NRK, our state broadcaster, and larger private media houses dispose of resources and routines for digital source criticism dedicated to rooting out biases, propaganda and (deep)fake news. That is obviously not done good enough. Even leading new channels publish editorials and commentary is rife with hypocrisy, blame games, cherry-picking logics, and muddled thinking about the incentive structures of great powers.

Let me return to our government’s international posturing of the Ukraine invasion.

Norway as Security Council Member in 2021-22 holds scant leverage in a largely paralyzed Council. Ambassador Juul has delivered statements holding Russia solely responsible, demanding suspension of operations and compliance with humanitarian law. Our Prime Minister Gahr Støre has delivered similar worded statements.

The government took a reasonable cautious stance on the extremely tangled issue of supplying military equipment. Norway contributed initially M72 mobile rockets, vests, helmets, and rations. Further support has been considered channeled through to the French brokered EU-mechanism “European Peace Facility Fund.”

The fund raises troubling legal and normative questions. Everybody’s focus is naturally now on Ukraine. Importantly, this mechanism aims at supplying aid and military equipment all over the world. Its alluring name represents a security and stabilization defined appropriation of “peace.”

Another reminder of how the international society currently maneuvers in murky legal and operative waters, driven by machinations of proxy warfare and nontransparent discourse, backed by claims of a “robust” framework of compliance and control measures. Norway may in the end not opt for the EU Peace Facility Fund, but an alternative Great Britain established mechanism.

This, according to government sources, offers better oversight and Ukrainian demand-based weapons acquisitions, but analysts have yet to verify such lofty claims and overall implication. An announcement from a The Time’s report this Tuesday 26/4 from UK’s Armed Forces Minister Heappey, says Ukraine can legitimately target military sites inside Russia from weapons supplied through external funds. That only looks look good for players intent on fueling an escalating war that transitions from proxy to direct engagements involving NATO.

Towards a Nordic defense compact:

Certain misconceptions persist among analysts and policy makers in Nepal and elsewhere in the South Asian region about Norway’s foreign and defense-policy. In Kathmandu, Dhaka and Delhi Norway’s standing as peace broker and peace maker remains reasonably intact.

Our High-North is imagined as an exemplary rule-based peaceful realm where Artic and non-Arctic states and indigenous organizations cooperate. Our special operation forces’ presence in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria are known amongst Nepalese policymakers and military officers. So are contributions to peacekeeping and peacemaking operations. The public at large is not aware how small Norway’s contributions have become meaningful since the late 1990s, since NATO-led operations have been given priority. Even fewer are aware that Norway is a sizable producer of rocket engines, weapon systems and ammunition. Norwegian war-industry companies contribute to the global production chain of the F-35 Lightening II of the American Lockheed Martin Corporation.

Norway is among the world’s 20 largest gun exporters. Following serious critique, a stricter export license policy is currently sought applied to export of weapons and military equipment.

The reality of Norway’s defense policy since the end of the first Cold War is one of radical reduction of our standing forces and of Heimvernet – a rapid mobilization force. Compulsory conscription in military service is abolished.

The Cold War’s classical mobilization-based invasion defense was substituted by a high-tech largely professionalized defense, including a mobile special force. This strategic redirection was in line with NATO’s new strategic concept of 1991 and the alliance’s Out-of-area Strategy of 1999.

The redirection and restructuring were also influenced by changes in military and civilian technology and domestic reforms, sugarcoated with slogans of modernization, efficiency, and effectiveness in a new era of no major wars but only civil wars. Finally, and not the least, neither voters nor politicians thought defense buildup required much serious debate beyond budgets that prioritized procurement of extremely expensive weapon platforms.

Arguably, this seems fitting for a nation projecting itself as an enabler and facilitator of peace. Today social media is rife with ironic and self-critical comments thriving on Norway’s illusionary perceptions of a lasting place and dramatic build-down of own defense. Scope for peace agendas, be they peace-brokerage, disarmament and a European deep-peace anchored security order seem awfully limited. Some commentators maintain Ukrainian heroism of resistance defending sovereign territory demonstrates the relevance of territorial defense and the importance of a will to defend and sacrifice.

Norway disposed by 2020 around 16, 000 military and civilian personnel, increasable to 63,000 in face of war. By comparison, Finland’s active personnel stands at about 22, 000. This is not much bigger than Norway’s. But Finland’s wartime military strength amounts to 280,000 personnel and a huge additional reserve force.

Since the Ukrainian conflict began in 2014, the Nordic states started to upscale military cooperation in situations of crisis and armed conflict. Finland and Sweden as non-NATO members, agreed on bilateral planning “beyond peacetime.”

In 2020 both countries and Norway signed a trilateral agreement at the garrison Porsangermoen close to the Russian border. The signing took place without any representative from Russia present. Last year NATO-members Norway and Denmark signed a similar agreement with Sweden. Short of a formalized alliance, the agreements endorse a Nordic alignment policy for both the High-North and southern maritime shores. The alignment might not be the end game of a Nordic compact as the non-NATO Nordics have in this period expanded military cooperation with NATO, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

The cooperation creates a foundation for further steps. For over a decade, the Swedish, Finnish, and Norwegian air forces conducted frequent joint training.

Recent opinion polls in Sweden and Finland are swinging towards solid majorities for NATO-membership. The parliaments are likely to vote this spring over eventual applications. Expanded Nordic memberships will revamp the Nordic and European geopolitics and security structure. Conventional strategic thinkers are largely positive; arguing Nordic deterrence (rather than a balancing vector of reassurance and deterrence) will be greater and better, and the Nordics’ thumb and footprint bigger within a more European-shouldered alliance.

However, arguments in favor of membership need to be challenged by counter arguments. Why does not NATO expansion onto Finland’s Russia 1,309 km/813 miles border and heavier footprint in the Baltic Sea increase the likelihood for NATO-Russian military confrontations by intent, misunderstanding or hacking?

One does not need to subscribe fully to the high priest of the realist school of thought John Mearsheimer’s account of the current crisis as largely caused over decades by the United States and its European allies. One may simply concede NATO’s enlargement is one if not the only root cause. Then, why would not a NATO-enlargement of the Scandinavian Peninsula turn into another delusionary overstretch?

Relevancy of the Nordics war experiences and geography assessing future risks:

This question is pressuring, requiring realist deliberations in the Nordic capitals and public life currently marked by alarmist tendencies risking premature decisions. One should also debate certain dissimilarities. They explain why Norway, Sweden and Finland chose different security policies after World War II. To a large extent, the differences are outcomes of different experiences during WW2.

Denmark and Norway chose neutrality but faced occupations by Nazi Germany. Finland initially fought a Soviet invasion in the Winter War of 1939–1940 and was later for a period on Germany’s side. Sweden escaped the horrors of war on a policy of a somewhat neutrality for survival reasons. This policy succeeded as Hitler did not need Swedish territory to realize his military objectives. The different strategic value of let’s say Norway stands unlike Sweden for an invader.

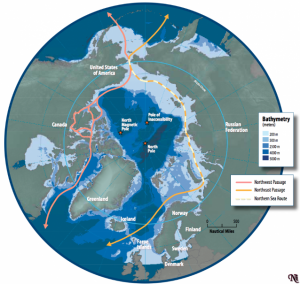

This should warrant a precise analysis grappling with geopolitics in a warming High-North. Russia’s Northern Fleet’s most important naval base is about 100 km from our border. Climate change is about to alter civilian destination and transit traffic along the Northern Sea Route and the other Northern passages. Russia has a legitimate right to defend and secure these recently modernized strategic military hubs and undertakes more complex exercises than before.

That includes Aerial mock attacks against the Pentagon-owned Norwegian Intelligence Service operated ball shaped Globus-II radar at Vardø, 28 km from the Russian border. A rotating reflector antenna receives information from satellites in geostationary orbit 40.000 kilometer away.

The Vardø Radar is most likely part of America’s advanced missile system. Although the Radar’s use is officially space observation and Arctic airspace monitoring for «national interest anchored in a longstanding bilateral US-Norwegian agreement. An expanded NATO presence is likely to inch military operations and high-tech installation systems close to the Finnish-Russian border, including the strategically important Kola Peninsula. That would increase the sub-region’s multi domain strategic importance and vulnerability, because of frighteningly short response time and as targets for first- or second strikes in case of a major conflict between Russia and America. Nor can one rule out spillover effects of a future multi domain military conflict in for example the South China Sea.

In conclusion, Nordic countries defense politics could possibly, before this spring ends and the midnight sun appear on May 20th – descend into a more unstable complex phase that may not end any time soon.

About the author: Tone Bleie is Professor of Public Policy and Cultural Understanding at UiT. Bleie’s work as consultant, manager, and applied researcher in and on Nepal, the Greater Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau spans three decades. Bleie can be reached at: tone.bleie@uit.no

Our contact email address is: editor.telegraphnepal@gmail.com